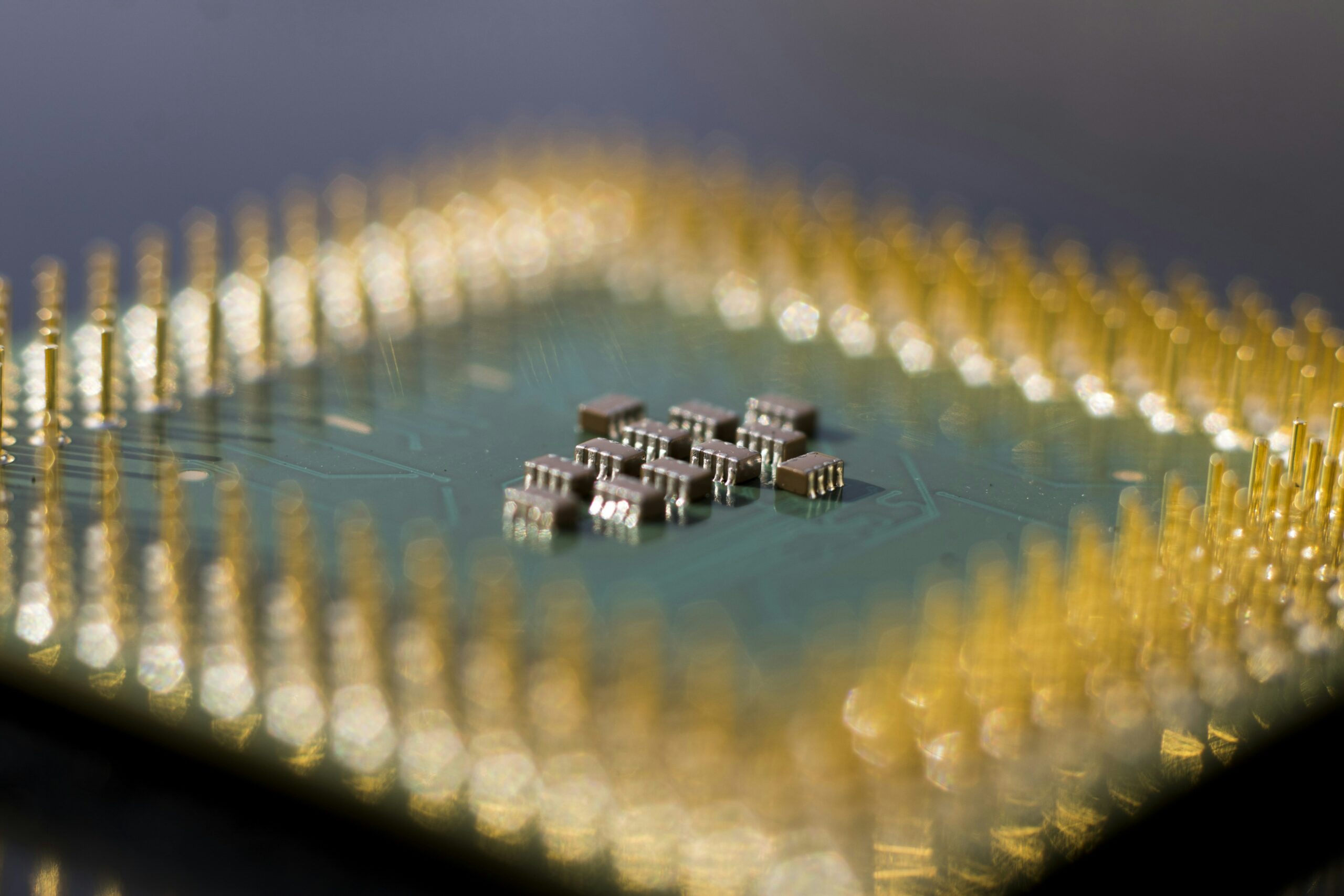

The worldwide shortage of semiconductors, critical components found in everything from smartphones to cars, continues to disrupt global manufacturing, prompting a critical reassessment of deeply ingrained international supply chain strategies. This persistent crisis, which began in earnest in late 2020 and has worsened sporadically since, underscores the fragility of just-in-time logistics and the geopolitical risks associated with concentrated manufacturing hubs.

The crisis stems from a perfect storm of converging factors. During the early stages of the pandemic, initial predictions of decreased consumer demand led major industries, particularly automotive manufacturers, to drastically cut their chip orders. Simultaneous massive global demand for personal electronics—laptops, webcams, and gaming consoles—driven by widespread remote work and schooling quickly absorbed available chip foundry capacity. When the automotive sector recovered faster than anticipated, it found itself at the back of a long queue for increasingly complex and specialized components.

The Fragility of Centralized Manufacturing

A significant element compounding the shortage is the extreme concentration of semiconductor production. Over 75% of the world’s chip manufacturing capacity is located in East Asia, with Taiwan’s Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC) dominating the most advanced fabrication processes. This geographical bottleneck introduces substantial vulnerability.

“Reliance on a single point of failure, especially in a region prone to natural disasters or geopolitical tensions, is no longer a viable business strategy for essential technology,” explains Dr. Lena Cho, an expert in global supply chain risk at the London School of Economics. “Companies are now paying the ultimate price for years of efficiency-driven, hyper-lean inventory practices that offered no buffer against unforeseen shocks.”

The repercussions are widespread. Vehicle manufacturers have idled production lines, resulting in millions of fewer cars, contributing significantly to rising consumer prices and inflation. Similarly, delays have impacted delivery times for essential medical equipment, networking gear infrastructure, and consumer electronics.

Investment Surges and Policy Shifts

In response, governments and major corporations are enacting ambitious policies aimed at diversifying production capacity. The United States and the European Union have prioritized major legislative packages—such as the US CHIPS and Science Act—earmarking billions in subsidies and tax incentives to attract semiconductor fabrication plants (fabs) back to domestic shores.

Intel, Samsung, and TSMC have all announced massive investments exceeding tens of billions of dollars to construct new, advanced factories in Arizona, Ohio, and throughout Europe. However, establishing a modern fab is a multi-year endeavour, requiring complex construction, highly specialized machinery, and skilled labor. Analysts suggest that significant relief from the current shortage may not materialize until the latter half of 2024 or even 2025.

Rethinking Future Resiliency

For industries reliant on semiconductors, the lessons centre on resiliency over sheer cost-efficiency. Actionable takeaways include:

- Strategic Stockpiling: Maintaining larger, albeit more expensive, inventories of critical components to weather unexpected supply disruptions.

- Supplier Diversification: Utilizing multiple vendors across various geographical regions for critical parts, even if the primary producer offers a lower unit cost.

- Design Changes: Modifying product designs to accept a wider range of interchangeable components, should specific chips become unavailable.

Ultimately, the global chip shortage is forcing a fundamental shift away from decades of globalization predicated on optimizing cost, moving toward a new era that prioritizes supply chain security and national technological sovereignty. While the immediate pain persists, the long-term trend points towards a more distributed, albeit more expensive, manufacturing landscape designed to be more resilient against future global disruptions.