The worldwide automotive industry is grappling with a severe microchip shortage, a crisis that has forced major manufacturers to slash production, delay new vehicle deliveries, and consequently drive up prices for consumers across established markets. Stemming primarily from unexpected pandemic-era demand shifts and persistent supply chain bottlenecks, this critical component deficit continues to disrupt nearly every facet of automobile manufacturing months after initial impacts were felt, reshaping global sales expectations.

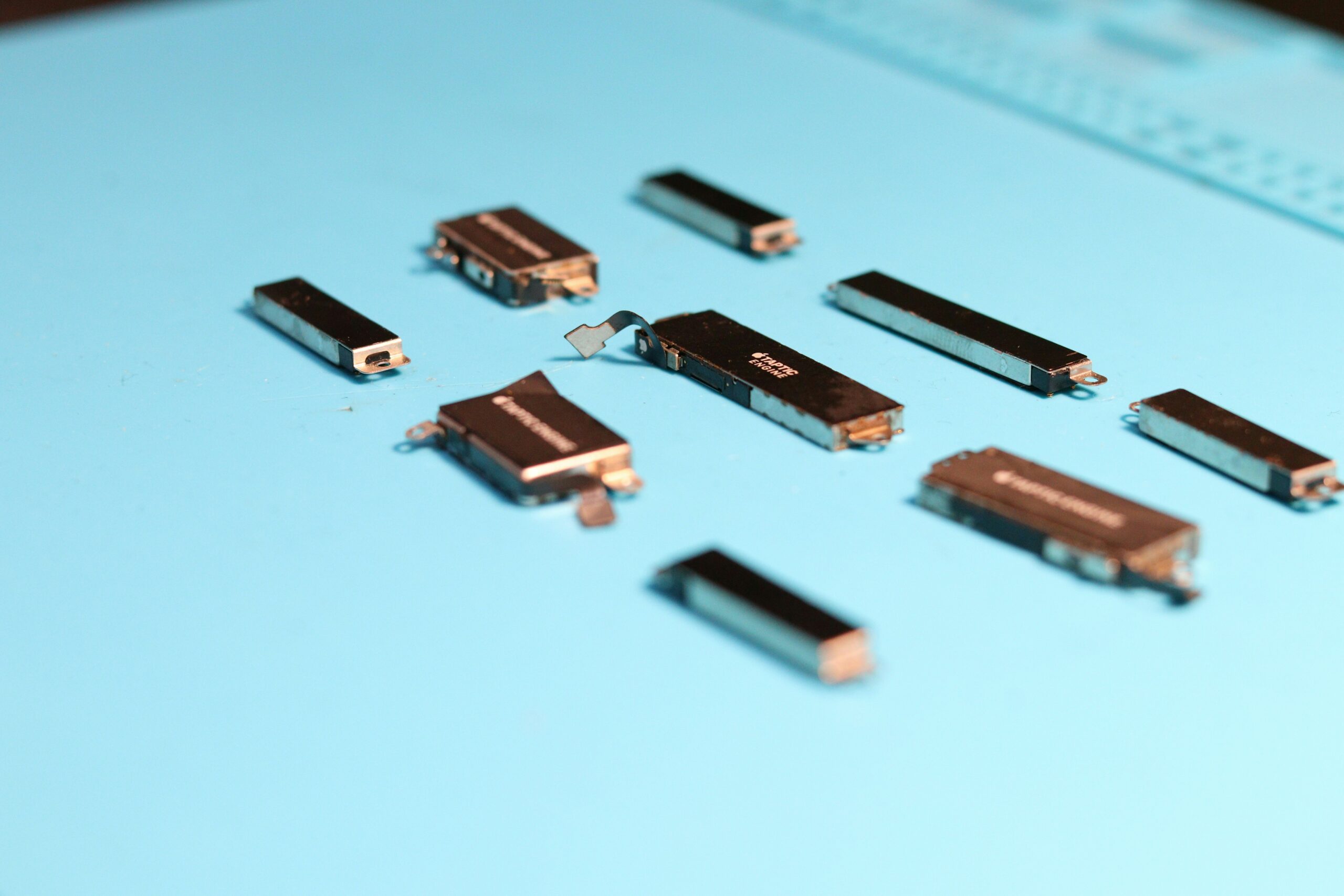

The root of the problem lies in the complex ecosystem of semiconductor manufacturing. Modern vehicles rely on dozens, sometimes hundreds, of sophisticated chips to manage everything from engine performance and battery charging to infotainment systems and advanced safety features. As global demand for personal electronics surged during lockdowns, chip foundries—already operating near maximum capacity—prioritized high-volume, high-margin sectors like smartphones, gaming consoles, and cloud computing infrastructure. When the automotive market rebounded faster than anticipated in late 2020, manufacturers found themselves at the back of the queue.

Industry analysts estimate that the chip scarcity has cost the global automotive sector billions in lost revenue, with figures fluctuating wildly based on geographical impact and individual company exposure. Major players, from mass-market producers to luxury brands, have been compelled to idle plants temporarily or ship vehicles incomplete, awaiting the arrival of crucial components to activate vital functions.

Impact on Consumers and Dealerships

For potential car buyers, the effects are immediate and stark. Dealership lots are showcasing significantly reduced inventory, leading to fiercely competitive pricing. Many consumers are finding themselves paying sticker price or above, a phenomenon rarely seen in non-luxury new car sales. Furthermore, the bottleneck is pushing prices up in the secondary market, with used car values soaring as buyers seek alternatives to long waits for new models.

“The traditional dealership model, relying on high volume and negotiated discounts, has been completely upended,” explains Fiona Chen, a supply chain economist specializing in industrial output. “Consumers need to prepare for fewer choices and longer lead times—often extending six months or more—for specific trims or high-tech options.”

This shortage is not merely about volume; it underscores a broader vulnerability in the global economy’s reliance on a few specialized fabrication plants, predominantly located in Asia. The chips used in cars are often older, less profitable designs than those found in high-end consumer electronics, making the automotive sector a less attractive customer for chipmakers during periods of peak demand.

Long-Term Implications for Manufacturing

In response, carmakers are taking unprecedented steps to secure future supply. Several major manufacturers have announced direct, long-term partnerships with semiconductor producers, bypassing traditional tiered suppliers in an effort to gain procurement priority. Simultaneously, policymakers in North America and Europe are exploring significant state investments to boost domestic chip fabrication capacity, aiming to increase self-sufficiency and mitigate future supply chain shocks.

While some stability is projected to return by late 2023, experts caution that the structural imbalances exposed by the pandemic will persist. The incident serves as a crucial lesson for global manufacturing: diversifying supply chains and integrating robust inventory management systems are paramount. For consumers planning a vehicle purchase, patience and flexibility regarding features will be essential until production fully normalizes.