A comprehensive new scientific assessment indicates that the Earth is absorbing significantly more energy from the sun than it is radiating back into space, a critical measurement known as Earth’s energy imbalance (EEI), which is driving the rapid acceleration of global warming. This imbalance, primarily caused by the accumulation of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere, is the fundamental metric quantifying the pace of climate change, with recent data revealing a near-doubling of the heat stored within the planet’s systems over the past two decades. Understanding this growing energy surplus is paramount for accurately forecasting future climate impacts and developing effective mitigation strategies.

Tracking the Planet’s Energy Surplus

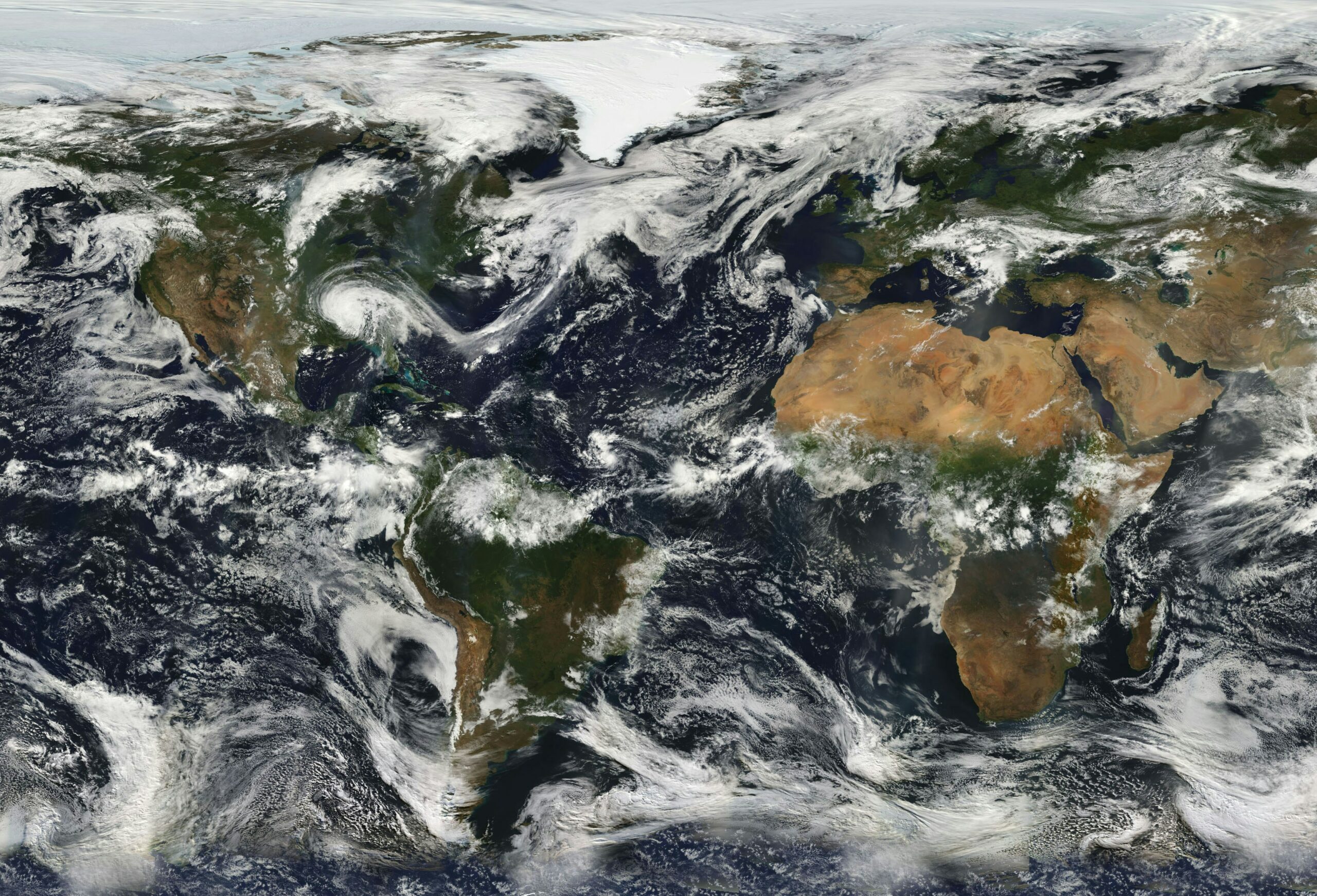

Scientists track the Earth’s energy budget by measuring four key components: incoming solar radiation, and outgoing thermal energy radiated by the Earth, both of which are primarily monitored by satellites. The vast majority—over 90%—of the resulting energy surplus is absorbed by the world’s oceans, making them the most crucial indicator of global warming’s pace. Smaller amounts of this excess heat melt glaciers and ice sheets, warm the land, and heat the atmosphere itself.

Recent analyses of the EEI suggest a marked increase, particularly since the early 2000s, moving from previously estimated levels to significantly higher figures. This acceleration implies that the rate of global warming is intensifying faster than many previous models projected. The primary mechanism driving this dangerous trend is the continuing buildup of atmospheric carbon dioxide, methane, and other greenhouse gases, which trap heat that would otherwise escape into space.

Why the Imbalance Is Intensifying

Multiple factors contribute to the escalating energy imbalance. While greenhouse gas concentrations remain the dominant issue, subtle shifts in cloud cover and atmospheric aerosols also play a role. Some highly reflective aerosols, particularly those generated by industrial pollution, have a temporary cooling effect. Efforts to clean up air pollution in some regions, while beneficial for public health, inadvertently reduce the reflective power of these aerosols, allowing more solar energy to reach the surface, thereby slightly contributing to the net warming effect.

Furthermore, natural factors, such as multi-decadal cycles of ocean heat content or minor variations in solar activity, usually have smaller, shorter-term impacts. However, the consistent, decades-long trend confirms that human activities are overwhelmingly responsible for the persistent and growing energy surplus.

Implications for Climate Action

The EEI serves as the clearest physical metric for gauging the severity of the climate crisis. If the planet is absorbing more heat, that energy must result in measurable consequences: rising sea temperatures, escalating sea levels, more intense weather events, and faster melting polar ice.

To stabilize the global climate, the EEI must be brought back to near-zero. This immense undertaking requires immediate and dramatic reductions in global greenhouse gas emissions. Every delay in emission reduction efforts compounds the problem because a higher EEI translates directly into a higher net stored heat content, increasing inertia in the climate system. Even if emissions were to cease tomorrow, the climate would take decades to fully respond as the oceans gradually release the stored excess energy.

Scientific institutions continue to refine measurements of the EEI, emphasizing the need for robust, long-term monitoring systems, including dedicated satellite missions and deep-ocean observation networks. These data are vital for policymakers to calibrate the necessary speed and scale of climate mitigation efforts required globally to avert the most catastrophic consequences of accelerated warming. The stark truth revealed by the EEI is that humanity is rapidly running out of time to rebalance Earth’s thermostat.